How To Be An Art Director 2: Knowing About Things You Don't Know About.

Being an art director is an ongoing education. Not only are you constantly pretending to understand new techniques and buzzwords (my fav this year: crepuscular rays!), but you’re also having to learn about everything that makes up the thematic elements of your game. And by “learn”, I mean “Google image search”. In my career, I’ve worked on games that take place in the highest mountains on the planet, big league ballparks, the streets of Moscow, lost jungle planets, the eastern front of WW2, and inhospitable mining planets in a distant galaxy (to name a few). And on each of those games, I’ve had an endless procession of artists come to me asking what I think things should look like: “What kind of traffic markings are there in a two lane commercial intersection?” “Where do you want the vents on the photon cannon?” “If those are meat-eating plants, shouldn’t the leaves be redder?” “What do you mean, Make it more farm-y?” “Are you cool with me taking Friday off?”

The amount of things these people think I know is staggering. If you knew me, you’d know I can’t change a lightbulb without consulting YouTube How-To videos. So it’s almost funny, when artists ask me if I want the superstructures built as steel- or tube-frame. Let’s just say I’m glad none of my calls on how things are built are looked at too closely by someone who knows what they’re doing. There’s a reason I don’t do manual labor, and it’s not just because of my soft, delicate hands.

When I was a young, dumb, zitty, insignificant artist like you, I always looked up to art directors. I thought they were the all knowing, all seeing visionaries who could tell you how every last pixel should look. The first art directors I worked with were experienced veterans, and they answered every question with an amazing amount of confidence. They could tell you what color the bark on a Douglas fir tree should be, or how streetlights should reflect off a slightly rusted ‘68 Mustang. In the rain. At dusk. These were smart guys. Much smarter than me, anyway. I didn’t know how I was ever supposed to know as much as I would need to in order to get a team of artists to actually listen to me. Seriously. Why would anyone listen to ME?

Eventually, though, I learned a very valuable lesson: Form an opinion, back it up, and wing it.

As an art director, you don’t have to know more than everyone (at least not the way I do it). You just need to provide clarity. See, the problem with Art, is that everyone has an opinion. This is something programmers don’t have to deal with. A producer has never walked up behind a programmer and said, “I saw this really cool line of code on Netflix the other night. You should try typing 10101 instead of 00110.” With everyone on the team providing feedback and opinions, artists can get pulled around in 20 different directions. That’s where you come in. You are the filter for all of the ideas the rest of the team wants to throw at the artists. You are their spleen. You absorb all of the junk, and filter it into useable ideas (that you take credit for). You keep them focused.

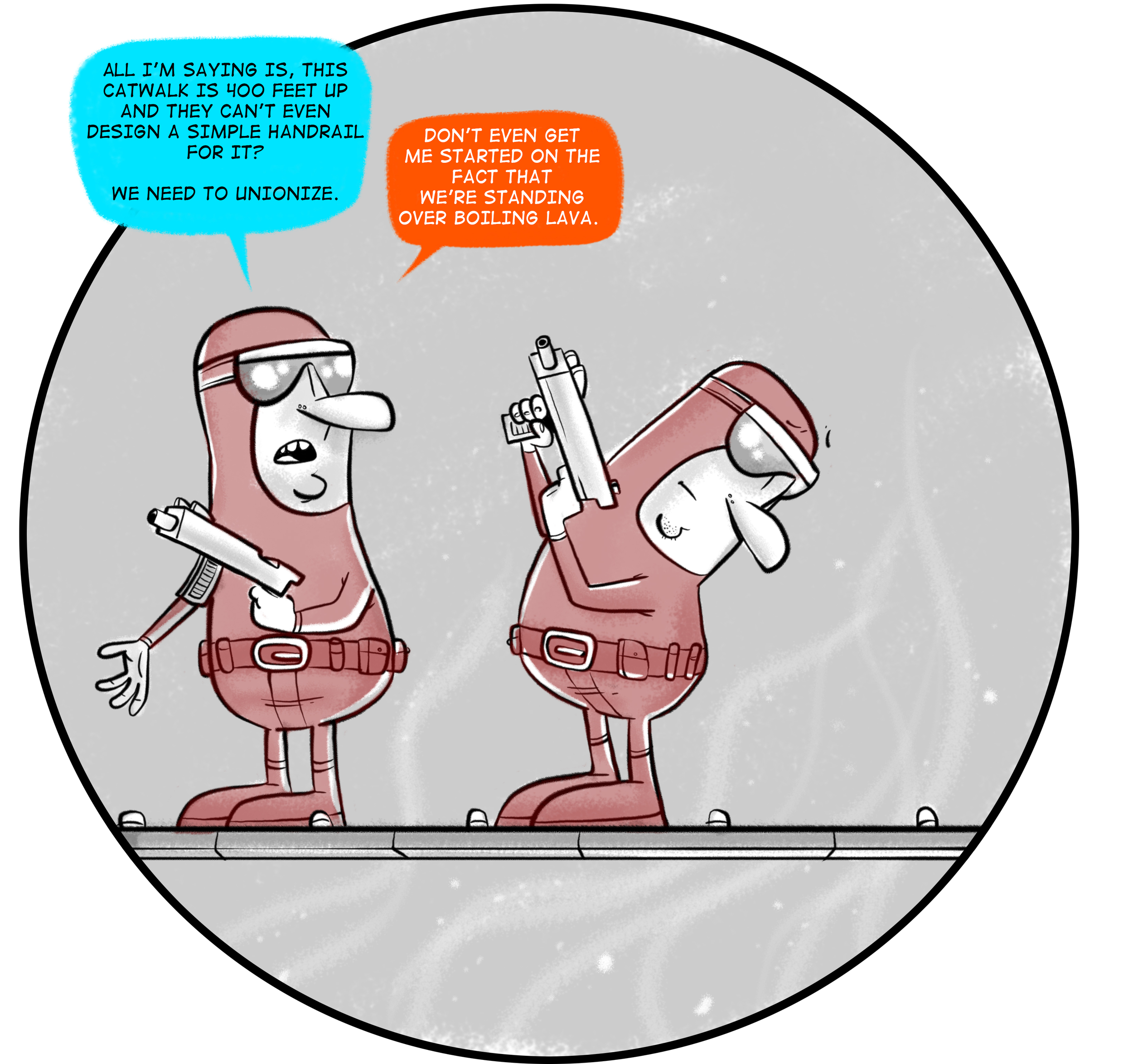

Once the game director has given the game an overall theme (Dystopian ice planet populated with marauding cyberhamsters, post apocalyptic urban wasteland ruled by snowboarding death squads), there are still a million questions to answer for every piece of art that goes into the game. Every day you’re going to be asked for your opinion. Beyond your ability to look good in all-black clothing, nothing is as important as your opinion. It doesn’t always have to be the RIGHT call. It just has to be a consistent call. I’ve made a lot of weird decisions as an art director that I’m amazed have gotten through. On one game, I suggested that a perfect location for the evil boss’ lair be on top of an active volcano. When someone asked me why anyone would do something so obviously stupid, I just mumbled something about thermal-dynamic electricity, and slowly backed out of the room. (The real reason, of course, was that everything looks cooler when it’s lit from below by boiling lava.

What to do when you don’t know

When you get stuck for an opinion (and you will), there are a few expressions I’ve found useful. If nothing else, they’ll buy you some time to scramble for a real answer.

1: “Interesting. Let me go check my reference sheets and I’ll come back to you.”

Translation: I didn’t even know you were doing this. Let me run to my desk, Google like a maniac for 5 minutes and get back to you, hopefully looking like I knew about this the whole time.”

2: Stare at the screen your artist has called you over to, rub your chin thoughtfully, and say, “Yes. I see what you’re doing there. But what does the (acid-spitting helmet/mummy’s tomb/3-headed cat) WANT to look like?”

After your artist stares at you incredulously, but BEFORE he or she says “Are you f’ing kidding me?”, glance at your phone, mumble something about having to pull assets together for marketing, and split.

3: “Look! Out the window! Is that Food Truck giving away free pulled pork sandwiches??”

This works every. Single. Time.

4: Two magic words: “Crepuscular Rays”.

This one works in almost every situation on unhappy producers. It sounds satisfyingly arty-farty, but not so technical that they SHOULDN’T know what they are, which prevents them from asking you what the hell you’re talking about.

Is your EP unimpressed with the concept art for the metal-bikini-clad space soldiers? “ I know, I know. But wait until we get the crepuscular rays on them!.”

Are your environments looking dull and flat? “Dude. Crepuscular rays.Pop. Wow. 95 Metacritic.” Did you completely blow the memory budget AGAIN by insisting every leaf on every tree have its own animation cycle? “Let me buy you a beer down at Crepuscular Ray’s and we’ll talk about it!” (Full Disclosure: I always thought Crepuscular Ray’s was a crab shack chain restaurant.)

5: When all else fails, Just say, “It’s a video game”.

Translation: It’s almost alpha. Ship it.